Halls of art contrasting the analytical. Unquestioned priors and halls of mirrors.

I attended the WeMoney Financial Wellness Summit on Monday and left early. It was held at an excellent venue — the NSW Art Gallery — where attendees mostly bypassed the artworks to hurry toward the next session on the agenda.

The architecture of the gallery luminous, the curations I got to be with, exquisite. And yet within its walls unfolded a language that felt curiously narrow to me in the time I was there.

I stayed long enough to hear Dan Ariely speak. He’s certainly an engaging storyteller. Funny, lucid, and generous in the way he translates behavioural economics into everyday language. The audience loved him. Yet as he described the biases and blind spots that shape our financial choices, and the metaphor of money as a calculator for opportunity cost, I couldn’t shake the feeling that something essential was missing.

The entire paradigm of behavioural economics still rests on the idea of the human as a predictable bundle of heuristics and errors. A creature to be nudged, modelled, or optimised. Behavioural economics, for all its insights (which I have used in much of work in the past decade in various ways), stops short of questioning the ontology that produces those behaviours. It speaks of irrationality but never of deeper meaning. It names cognitive bias but not moral blindness and injury in the deeper layers of our cybernetic systems. It maps decision-making while ignoring the wound in our social perception that makes such mapping necessary.

The talk from Dan, though intellectually clever, fell somewhat flat for me.

The unspoken assumption was that if only we could design better incentives, we could fix the system and economically liberate people. As though human flourishing were an financial engineering, behavioural economics and policy problem. I found myself longing to ask Dan a question of a deeper reckoning with the inner and outer architectures of value. Alas, we don’t get to converse with Keynote speakers in these formats. It’s a summit, not an un-conference, I reminded myself.

The panels I attended spoke of inclusion but talked primarily of operational efficiency, and of how AI was used for automation and building agents to replace the conversations they would usually have with humans. Of using the technologies to educate people and build financial literacy. Of creating playful interfaces to engage consumers to learn about how they spend money and take ownership of their financial lives. Titles of panel talks with words likes empowerment, yet the central substance was about using data to create more seamless and frictionless consumption in a worldview with no biospheric limits.

I waited for someone to ask what good means, or how financial wellbeing can exist on a planet in overshoot. No one did. My hand raised being the one that didn’t get airtime because the timer was up. The words “responsibility” and “future generations” remained absent from what I witnessed, as if they belonged to another conference or timeline of reality altogether.

One session framed “AI and Financial Inclusion” mostly as a productivity revolution. Another, titled “Data for Good”, centred on proving the commercial viability of the Consumer Data Right. A framework I once championed for its radical potential to re-imagine data sharing ecosystems and the future of our phygital society. Listening in, I felt both affection and some grief. Affection for the dream that it might have been different and grief that the dream had been domesticated into language of compliance with the status quo.

After a while, the air felt thin. The vocabulary of wellness was managerial. The moral imagination, dull. I needed to breathe.

So I went and consulted with the plant elders out the front of the gallery. Epic Moreton Bay figs that exude presence and patience.

But I had actually arrived a little before midday while a session was just wrapping up and instead of going in with a friend to hear the final words of that session I decided to wander into the library. The main archives were closed, but the children’s library section was open. I mindfully noted this as an invitation to wonder. Parents read stories to their children as their chirps of curiosity made the space feel quietly alive. At a small table sat a box of fat, coloured pencils, and blank sheets of paper. They called to me. And I drew something in that brief few minutes that upon later reflection, spoke symbolic volumes about what I was to then bear witness to over the coming hours at the summit.

The Drawing

I sat down at the children’s table, the one meant for small bodies and curious minds less tethered to the conventional expectations of “adult” logic. The box of pencils was a cheerful mess. Fat tips, many blunt or cracked. The kind that refuse precision. I picked up a brown pencil and began to move it across the page without knowing why. The hand and heart mind led.

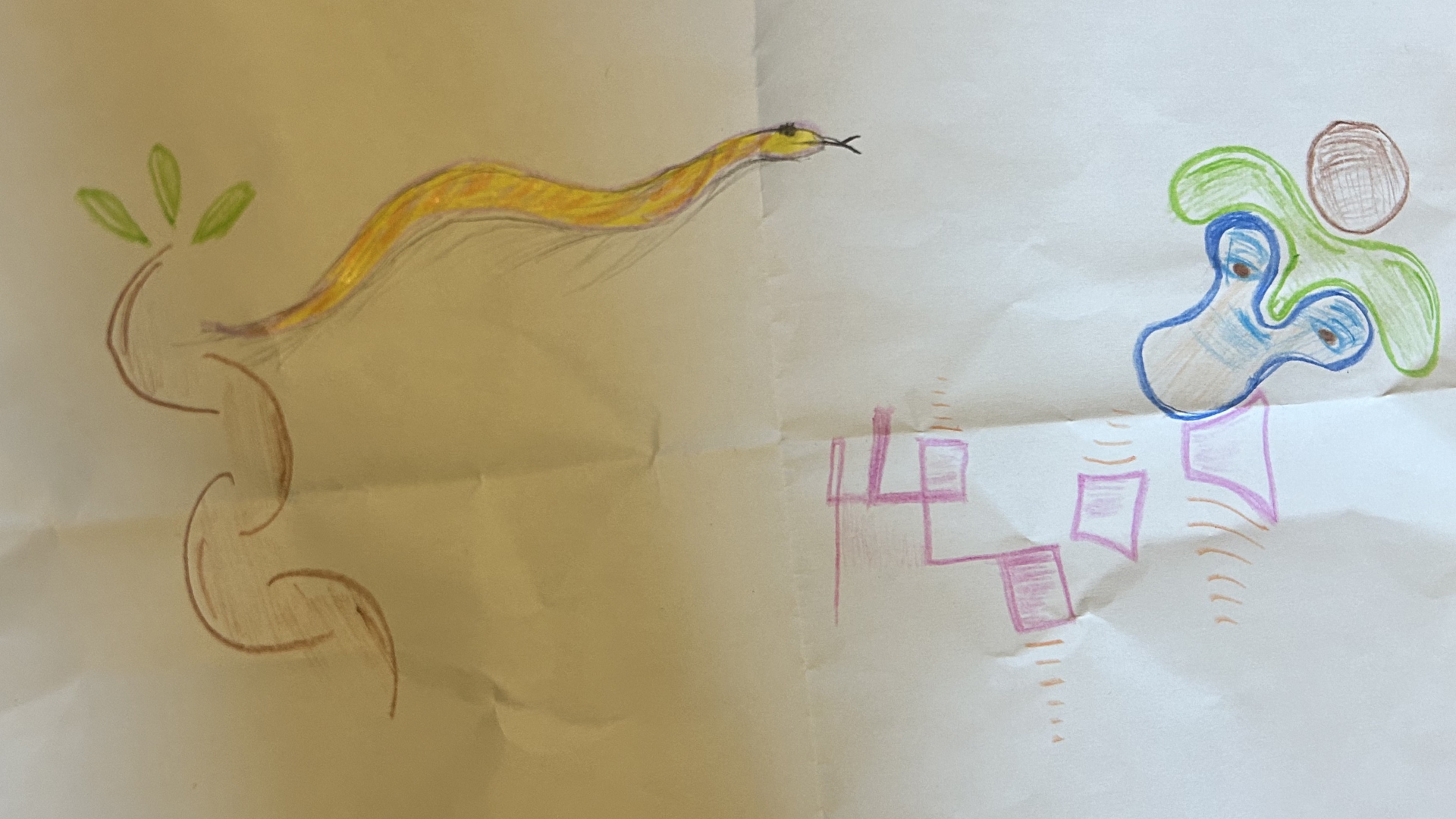

A plant emerged first, a curved stem rising from below, three leaves branching upward. Then a serpent appeared, flowing from left to right, its body a ribbon of gold, purple, black and orange. At the far edge, an abstract face-like form took shape amid blue and green swirls, surrounded by pink geometric fragments that softened as they approached it, curving and blending until they dissolved into the being itself.

I didn’t think of money, or AI, or inclusion. I didn’t “think” at all really in the conventional sense. The page became symbols of the ecosystem I’d intra-acted with for many years. Root and leaf, serpent and cell, structure and emergence. It seemed to carry the day’s real conversation I was present for, the one unspoken in the summit panel rooms, the main theatre, or conversation over lunch. How life continually seeks to reconcile what the human mind keeps dividing.

Later, when I laid the drawing beside my summit lanyard — “Mat Mytka, Moral Imagineer” — the symbolism struck me. One, the credential that grants access to the institutional world. Then other, a spontaneous map of becoming. The sanctioned identity and the living imagination, side by side. The contrast was almost comic, I thought to myself as I took the picture.

Yet it was quietly sacred too.

What had felt like boredom at the event now revealed itself as a kind of grief. Not for the people who spoke, the organisers, or the attendees. Many were earnest and it was nice to catchup with some fellow human Earthians.

My grief was for the enclosures of imagination that the fintech paradigm demands. And perhaps, too, for my own complicity and naivety in once believing that frameworks like the Consumer Data Right and Open Data Ecosystems could change the world from within the same epistemic architecture that produces its harms.

Sitting there, drawing with children’s pencils in what might be seen as a colonial temple of art, I realised that imagination is the only ledger that still balances. The only economy that regenerates itself through use.

The way home

On the way home, I thought about what passes for inclusion in financial systems and what it costs us to keep believing that the next platform, the next metric, the next financial innovation, will redeem us. We talk about trust and literacy and access. Yet these are the very words for the symptoms of the sickness. The real deficit isn’t data sharing frameworks or education. The gini co-efficient or how many people in sub-saharan Africa are “un-banked”. It’s relational. We’ve mistaken coherence and connection for computation and vectors in a data store.

Around the corner from my home I said hello to Carlos while he was cleaning his work truck. Mentioning we recently had a good harvest of bananas and that I would bring him some. Closer to home my next door neighbour, Tony was tinkering in his garage. We spoke to the mango tree, saying they looked happy that they were getting more sunlight this season. He said he’d help with some gardening and tending to the front pathway. I brought him some bananas and he gave me some Chinese biscuits for the kids. Small acts, and older relational currency that transcends technocratic enclosure.

It struck me that this was the view of economy I’d been craving all day. One rooted in reciprocity and relationship rather than frictionless exchange. No consent dashboards, no behavioural models, just an unspoken rhythm of giving and receiving that renews itself with every gesture.

The drawing from the children’s library lay on the table inside my home office, next to the lanyard with my printed name. In that quiet moment they seemed to belong together. The credential of the fintech ecosystem and the sketch of another world gesturing toward what might yet be remembered.

Maybe the future of financial wellness won’t emerge from summits or regulatory sandboxes? Maybe it comes from the spaces in between that are less captured by institutions that are slowly ossifying. Like the community gardens, spontaneous neighbourly conversations, and the small acts of reciprocity where imagination and relational trust are still intact? I actively hope so.